The Research Leaders

"The whole purpose of all nursing research is the patient… (The more research we do in the discipline of nursing, the more data we have to support the patient)."

Intro

Over the past few decades, life expectancy in much of the developed world has steadily increased. An average 65-year-old in the US can now reasonably expect to live well in to their 80s. While this is to be celebrated, an older population also means a growing need for healthcare and support, potentially placing a huge cost and time burden on societies and individuals. Finding ways of making sure that we not only live longer but also that those lives are rewarding and healthy is going to be critical. And here, the field of nursing research has a central role to play.

Nursing is often viewed as a profession of bedside care - looking after the ill and vulnerable, and carrying out instructions handed down by physicians. However, the role of nurses in advancing patient care is far broader the that. A global community of interdisciplinary researchers are engaged in innovative projects which take a holistic approach to patient care, looking at not just the disease or health condition but the whole person, their lifestyle, their community, their social and emotional needs.

The University of Minnesota School of Nursing is one of the leading voices in this research. Its staff and students, and alumni around the world, are working on groundbreaking projects which aim to address the very real nursing and healthcare challenges facing societies, like reducing stroke and falls risks, tackling the growing problem of dementia in an aging population, and exploring how mindfulness can help people deal with chronic health conditions.

Nursing research is !not about being an extension of physicians,” says Dr Niloufar Hadidi, an advanced practice nurse and associate professor at the University of Minnesota. "It's a discipline by itself”, merging the science of nursing and research and data collection to “provide us a foundation by which we can help the whole person”.

Harnessing tech to stave off cognitive decline

As the population gets older, diseases like dementia are becoming a "huge, huge issue”, says Dr Dereck Salisbury, assistant professor at the University of Minnesota. Close to six million people in the US suffer from Alzheimer’s dementia, while an estimated 50-80% of people over the age of 70, when asked, report some degree of *subjective cognitive decline”. The latter is a preclinical risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, where the person perceives they are having problems with their memory, despite performing normally on cognition tests. It's not only a public health burden in the US, it's a global health burden, says Dr Salisbury.

“And it affects a lot of different people within the family and the healthcare community. The health care costs of dementia, particularly related to Alzheimer's disease, are very staggering.” With no known cure, early intervention is critical to slow the progress of Alzheimer’s disease. Studies suggest that delaying the onset of Alzheimer's disease by five years could save the US alone an estimated $258bn (£195bn) by 2040.

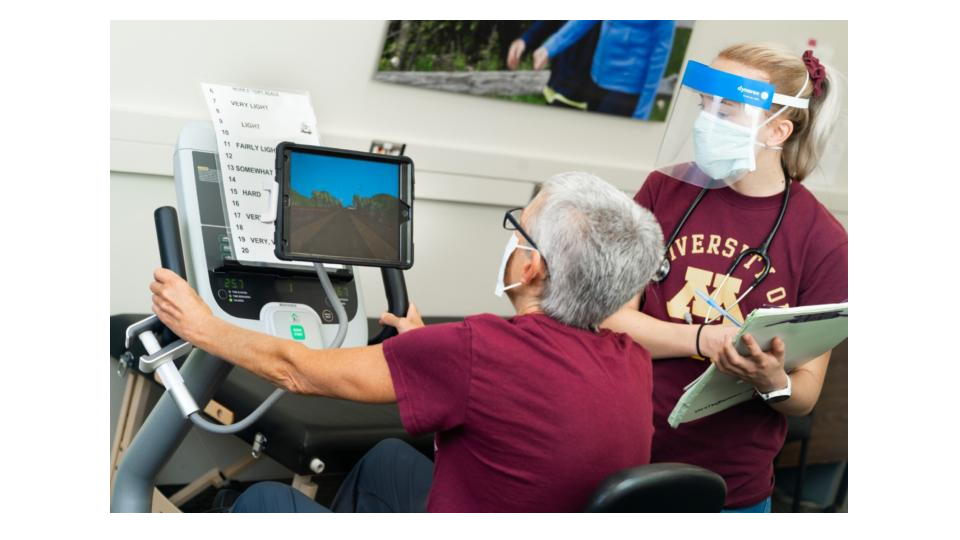

It's well known that physical and cognitive activity are vital for staving off cognitive decline, but less is known about the benefits of doing both at the same time. Salisbury has drawn on his background in kinesiology – the study of human movement – and the nursing research expertise at Minnesota to develop the innovative Exergame Study, which is using

nursing research techniques to explore just that idea.

His team at UMN have recruited 40 participants aged 65 or over - the oldest is 91 - who self-report some level of subjective cognitive decline. In regular sessions over a period of three months, they're asked to ride a recumbent exercise bike while virtually navigating a landscape on a tablet, periodically solving brain teasers that pop up. Their fitness and cognition are then tested and compared to control groups.

Early indications suggest that Exergame is certainly helping to reduce some of the social or emotional barriers people feel about taking part in exercise. "Our participants really have great and positive things to say about our staff and our interventions, how they improve their daily life,” says Dr Salisbury. But they're also hoping it will show increased cardio-respiratory and cognition benefits too, findings which could have a significant real world

impact.

"The longer we can live without disease, the better our long term quality of life is going to be,” says Dr Salisbury. "I think that is at the forefront of what nursing research is really about and how it can really positively impact our communities.”

A curiosity mindset

I would say the mindset to bring to nursing research is one of curiosity. Also a drive to make things better,” says Dr Siobhan McMahon, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota, with a background in gerontological nursing. Her own research was inspired by personal tragedy, when her grandfather had a fall that triggered a cascade of complications, and eventually led to his death.

"Then in my nursing practice I was seeing a lot of people suffer from falls,” she says.

Official data shows that falls are in fact the leading cause of injury death in people over 65s in the US, generating healthcare costs of $50bn every year. But Dr McMahon says falls need not be an inevitable part of life for older people, a group she refers to as “our

treasured elders”. Often, it’s just that the advice on how to prevent falls hasn't been properly communicated to those who need it most.

Older people at risk of falling might be getting a wealth of knowledge from their physicians and nurses, like which exercises they should be doing, but Dr McMahon says that as with any change in health behaviour or lifestyle, there will be many barriers and challenges in

place for patients to increasing their exercise or physical activity. Identifying how to help patients overcome those barriers is the core of her research.

As a nurse, Dr McMahon’s instinct was to think about the patient experience. So her research began by simply listening to older people, and setting up groups in which they could discuss their experiences of physicians and the fall prevention advice they had received and why it hadn't worked for them.

"Participants in some of our research groups do a lot of collaborative learning to process, compare experiences, and troubleshoot together,” she says. They might talk about times they have smiled and nodded at their doctor to be polite, knowing they will struggle to take up their advice, or share the ways that they have juggled trying to stay active for their health, with avoiding the risk of falling.

"One of our studies showed that strategies which involve interaction - interpersonal interaction with peers - help people increase their physical activity more than strategies that don’t involve these interpersonal interactions,” says Dr McMahon. This has enabled

her to develop unique sets of interpersonal behaviour change strategies, to help people incorporate fall-reducing exercises into their everyday lives, that she is now testing in a large, community-based study.

Participants say the programme has been life-changing, giving them the space and support to integrate exercise into their daily lives, some of them for the first time ever. For some, the experience of just being listened to was in itself restorative. "I had a woman tell me the other day: I'm so grateful that you came to us [to do this research]. As older people in the community nobody wants to hear from us,” says Dr McMahon. "When they're in their groups and talking they trust each other. That holds a lot of power.”

Whole person means whole community

The research by Dr Niloufar Hadidi, a leading expert in stroke prevention and rehabilitation at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing, aptly demonstrates this art of working with patients, to deliver findings which are of genuine, practical use. "Nursing research goes back to what evidence we can provide to move the nursing science forward,” says Dr Hadidi. It's about taking a whole person” view of the patient, including the emotional, psychosocial, environmental and spiritual context of their health needs.

When she became interested in developing stroke prevention strategies among African Americans - who are twice as likely to suffer a stroke as their white counterparts - involving the community in the research process was essential.

Dr Hadidi and her interdisciplinary colleagues began by recruiting community health workers with strong local connections to be part of their research team. These volunteers then worked alongside the researchers to help them really understand how to approach the community, and what barriers were preventing people from accessing and adopting health advice on how to prevent strokes.

"Building trust is such a big issue and first step,” says Dr Hadidi. Community members told her how researchers in the past would turn up, observe them and then leave, leaving them feeling no better off. But the health workers !were instrumental in bridging conversations that we had with the community,” says Dr Hadidi, enabling people to see how it would benefit them to share their experiences and use them to help others. Ultimately 54 participants were recruited for focus groups, piloting new stroke awareness strategies. The next stage will be to train up a team of volunteer !stroke champions” to carry on the health campaign after the researchers have moved on. "We want them to have the ownership of this,” says Dr Hadidi. "That's how it exponentially grows.”

Dr Hadidi says engaging the community in her research has been both rewarding and eye opening for her and empowering for the participants. By listening to the community and responding to their needs, rather than assuming expertise, the team demonstrated to them that they have "strengths within the community, that they can reach out and actually be

part of the solution”.

Researching the healing power of mindfulness

Dr Roni Evans is an associate professor and the Director of the Integrative Health & Wellbeing Research Program at the University of Minnesota’s Earl E. Bakken Center for Spirituality & Healing. She is a chiropractic clinician by training and a clinical researcher in pain and chronic health conditions. Throughout her career she has explored how to help patients cope with ongoing pain, something that can be a very elusive problem to clinically resolve. Pain can cause patients a great deal of emotional distress and worry, she says, as they become scared about how it will affect their job or relationships.

For older people, the fear of getting injured can even put them off physical activity altogether, which may ultimately only worsen their underlying health conditions.

Dr Evans says there's often frustration among physicians that patients don't follow health advice they're given, even when it's in their best interests. For example, by doing specific exercises designed to help with their pain. Her research is exploring how mindfulness - developing a stronger awareness of the self, and the connection between the mind and the body - can be used as a tool to help patients engage in positive pain management behaviours.

This is one way that can help overcome some of the barriers to patients not doing those things that are good for their health and wellbeing and it's actually a tool to support them and also the clinicians who want these things for their patients. So I am hopeful.”

Advanced nursing research is quite simply, !a matter of life and death”, which makes an essential contribution to the global healthcare profession, says Dr Kuei-Min Chen, an alumnus of the University of Minnesota who is now professor at the College of Nursing at Kaohsiung Medical University in Taiwan and director of its Centre of Long Term Care Research. It is really important to not just educate our new nurses to know how to take care of others but in addition, we have to empower them. You also have to have the ability to generate new ideas or generate knowledge,” she says. "Through research, we can find innovative methodologies, in addition to medication, to help [patients] relieve their symptoms.”

Dr Chen has used her personal fascination with the ancient art of tai chi to research how to encourage older people in Taiwan - which is reaching crisis point with its rapidly ageing population - to stay active for the sake of their health. When she began her studies in 1999, she could find only 40 papers in the whole world which addressed the benefits of tai chi on health. "That was why I designed rigorous studies to really test the outcome of tai chi and build up the evidence-based outcomes,” she says. In the following two decades, Dr Chen has become a world expert in developing tai chi and yoga practices and teaching which appeal to and work for older people, with demonstrable improvements in their health.

Like all nursing researchers, her work isn't about coming up with quick fixes, or patching up patients and leaving them to carry on with their lives. It's about truly understanding their needs and supporting them through making gradual, manageable changes to their lifestyle, which bring long-lasting and maintainable results. As part of her research, she trains up community volunteers who can teach yoga and tai chi to older people, and in helping test out her theories and new approaches, can then carry on teaching when the research period ends. "Beyond the research, we hope this programme can be a part of their life,” she says. "No matter what stage your health is right now, you all have the potential and ability to promote or maintain your health status.”

Dr Chen and other nursing researchers are deeply proud of what their work achieves and how it contributes to the global healthcare community. She is also grateful for the worldwide network of researchers and their constant innovations on behalf of patients. "People see nurses as helpers: we take care of patients, we try to ease their symptoms,” says Dr Chen. "But actually, nursing is a profession, truly a profession. We are not just taking orders from physicians.” Nursing researchers have their own vital and independent role to play, she says. All of which contributes to helping patients around the world live those longer, happier and healthier lives.